Cinematographer and Technical Director Christopher Webb has been shooting design-driven work drawing from multiple disciplines for over a decade. Together with founding partner, Graceann Dorse, Chris has built a studio to focus on this work full time. FX WRX specializes in cinematographic effects magic that derives from in-camera shooting. Their work has garnered multiple Promax Broadcast Design Global Excellence Awards and an Emmy.

Throughout his career he’s remained fascinated by the possibilities of in-camera approaches. “I’d seen stills of Richard Edlund, ASC, doing the Star Wars typography with characters etched into black,” he recalls, “and the DykstraFlex motion-control camera moving over it as Richard programmed a hard-wired camera move. That opened my eyes to how technology could expand things while also getting to the root of cinematography, and how in-camera lets you wield tools in an exploratory way.

A Little of This, a Little of That

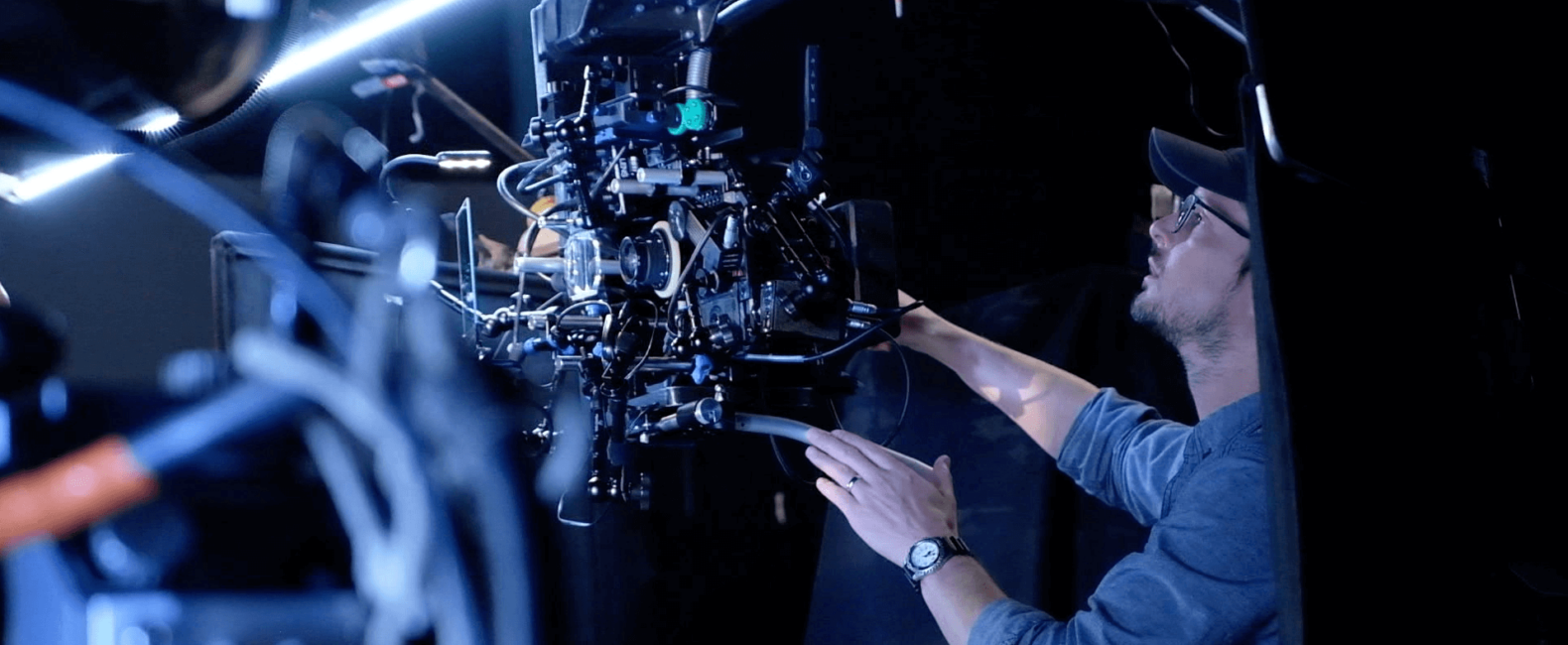

Webb’s explorations often began by finding ‘happy accidents’ during a process of visual discovery, which became part of the methodology at FX WRX. “R&D is where we look to start introducing accidents into the process, so it doesn’t become too nailed-down,” he notes. “We’ve gotten into a mode where our A-game projects become little journeys of exploration. I’ll build Lego models of the rigging to prove things out, then have a crew in to build it for real as the art department researches materials and textures. When embarking on this scavenger hunt, we can see right away if something doesn’t work or just isn’t exciting, and go right to a backup idea to find the answer.”

Shoots are usually of two to four days duration. “We’ll often be moving the camera through landscapes — sometimes in the form of miniature sets — animated via light play,” he elaborates. “We’ll often have laser-cut typography, or lettering that is etched into glass or constructed dimensionally. And for conveying unique perspectives, there might be a probe lens. Optically, I might introduce a physical element that creates the impression of a streak filter, then layer that atop the typography while animating the result with a simple puppet motor rigged light to make it come alive. These additions take your shot past, ‘that’s a cool miniature shot’ or ‘great slow-motion’, and helps the work become multifaceted and unique to each project.”

After setting up his first shop, Webb discovered that many creative directors and designers found his ideas for using cinematography in title sequences and motion design appealing. “It took them away from the computer and put them in that experimental space where there’s room for discovery,” he reports. From that initial group of motion designers, interest in Webb’s work expanded to those on the commercial side more interested in the design and branding of whole product lines and brands. “That exposed us for doing campaigns, rather than just, ‘we need a tabletop shot of this item,’” he relates. “We stressed our approach was about developing techniques that yielded good in-camera processes, so shooting lots of takes generates an abundance of good material. If a broadcaster wanted to brand a whole year’s worth of images for their network — titles, IDs, bumpers, an ‘on-air tonight’ and various graphics — that could take a lot of time and money if you’re working in the established pattern, whereas we can generate all those elements in a three or four -day shoot.” Webb’s work for Trollbäck+Comany on USA’s Mr. Robot illustrates this approach. “USA aired our material for two seasons worth of branding – and that was all from one shoot.”

The Best of Both Worlds

The Mr. Robot imagery relied on a mechanically-driven optical table, allowing decades-old filters made in France to be passed in front of prisms displaying projected imagery of the Empire State Building, all of which could be manipulated in real-time. “Like jazz, you’re responding in the moment to what is going on around you with the other artists and the mood of a place,” Webb enthuses. “That’s exciting to me, and often more effective than proceeding in a clear-cut linear fashion. “We’ve been working with retro-reflective screens, along with LED screens and beamsplitters [glass with qualities of both reflectance and transparency that facilitate single-pass in-camera magic] and found-footage for a long time. We can play with the color story by putting imagery into a practical environment where elements are getting refracted, which lets us create a unique kind of universe around the material.”

Webb firmly believes that a mix of analog and digital approaches often generates superior results. “There’s a perceived difference between in-camera effects and CG visual effects, but I found myself in the position of saying, ‘no – it’s all visual effects,’ he declares. “When we get a killer CG artist on set with us who sees what we can do, it gets them excited. The melding of techniques can bring artists together into an experiential set where they can respond to things with creative energy, while there are also practical economic aspects in achieving efficiency.”

Outbreaks & Out West

Though a demo reel is de rigueur in the business, FX WRX prefers to put a different foot forward. “We try to show our Art and Process film,” Webb explains, “because revealing the behind-the-scenes can communicate what we do better than the finished work. He cites the FX WRX work on viral-outbreak series The Passage, for which promotional and title sequence elements utilizing found materials and the show’s cast came out of a single shoot. “One check box on this particular treasure hunt was natural objects, so our art director brought in plants, skulls and these twisted-up little sticks. I wasn’t initially sure it would amount to much. We arranged them around our Innovision Optics probe lens, then got backlight passing through them, which created streaks suggesting a self-animated quality. It was a look that you could characterize as nonspecific – which is the hardest thing to achieve. The compositors saw and built on this, creating a whole circular eye pattern, an iris with pupil in the center, and that became the main graphic for the show.”Webb’s crew had rigged both interactive light gags and image-distorting rigs to capture the show’s cast members when they were brought to the studio. “My lighting tech had a big LED blade on a puppet rig flying over the talent, animating the light falling on them,” he reveals. “That presence gives the actress a sense of how the timing works, and as she turns, I cue my assistant to activate motors moving a reflective element across the lens, which pulls her out of the image like she had been erased by some strange power. I was operating our 6K RED on a mini-jib so as to fly the camera by hand, which gives the whole thing a very tactile aspect, combining motorized precision with inspiration occurring on the fly.”

For the repeatable aspects, FX WRX often uses Kessler motion-control gear. “I can take their low-cost, high-value equipment apart to use the CineDrive motor block module, then go to my rigging crew and ask them to put another axis of movement on. You can buy a beautiful motion control head for a couple thousand bucks. So I can afford to put that on my Cricket dolly from the 1960s, and it is a perfect combo for many jobs.” For the opening and transitions into segments of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, FX WRX helped titles and VFX company Big Film Design capture the age-old turning of story book pages as a cinematic element. “The Coen Brothers are, so far as I can tell, not fond of motion control,” ventures Webb. “Maybe that is because the process is so linear, with talking to the operator, then making a programming change. But Joel liked responding in the moment while at the monitor, giving direction or holding up a hand to indicate slow down, stop or speed up. and respond. That hands-on aspect is part of what makes Joel and Ethan such amazing directors.

“I had shot mockups of the book with my manual jib arm, on a RED and a 40mm Arri Macro,” Webb continues. “The response was, ‘Okay Chris, you nailed it. Now do all seven scenes the same way. I had done myself a disservice, because they thought I could do the whole movie — which was at picture-lock and edited to time-code — that way. I told them that it took me a whole day to get that single mockup shot, and that there’s no way for me to do this on-set with you without motion control – which they didn’t want and also couldn’t afford it at that point. So the TechnoDolly provided and operated by [Reality VFX] was a perfect solution. We could find key frames manually, then finesse the look. And if Joel wanted it faster or slower or to change some aspect, the control was right there in hand to make it happen, and that input would be added to the move. That was a process of finding the right tool for the way they wanted to work.”

Sneakers & Fragrances

Sometimes the degree to which post VFX will be required can vary, depending on the ingenuity that goes into the production shoot. For a Timberland shoe spot, Webb and associates were initially only tasked with blasting some smoke past camera and some interactive light on the product, which is supposed to be plummeting downward through a thunderstorm. [VFX vendor] MPC came here to shoot smoke plates with us, but I suggested that in addition to the chaotic atmosphere, we could put the camera on a bungie and shake the heck out of it while shooting slow-shutter, all the while maneuvering the sneaker on a motion control head that allowed it to tumble. In this way, we got completed shots in-camera, though the workflow was originally to be mostly postproduction CG VFX.”

In the case of FX WRX’s work for Calvin Klein, Webb was delighted to hear from many CG artists who thought his practical work – which involved choreographing the flight of ribbons around the product — was actually CG! “The beauty of that was how we built rigs to launch the ribbon. Using a V-shaped trough, we coiled the ribbon back and forth in little loops so it stood on edge. When it emerged, it would stretch out in a dynamic way as it transformed into this cool flying dragon of ribbon.” The other bit of magic came courtesy of a controlled air valve on the other side of the bottle. “This air knife caused the ribbon to deform as it approached the product, seeming to hesitate and flutter, almost like there was a force field around it. That specific kind of controlled turbulence wasn’t the objective at first, but did employ a methodology we felt worth trying, and the results were so much better than anything we could have meticulously planned for. On the business side, it was great because it was all there in-camera, without the usual huge approval process going on for weeks, which is often the case with computer graphics.”

While FX WRX embraces new gadgets when appropriate, often fashioning their own, Webb still tries to avoid the crutch of embracing the latest shiny thing. “Everybody wants to put a high-speed Phantom camera on a robot arm while breaking or splashing something,” he says, “whereas we’re trying to find ways to get back to the craft instead of falling into a technology/gimmick-based approach. Again, this is like jazz, because you’re getting in tune on the fly and discovering the magic as you go. If you program everything, you’re only ever going to get what you program, putting limits on the results. Why use that robot arm when I just need a stick, or just hang a jib arm off the ceiling with a flashlight attached?”

Stick-based and other seat-of-the-pants solutions fit right in with another Webb inspiration, evidenced by models in his office of experimental aircraft, including the X-1 flown by Chuck Yeager in events documented by Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff and Philip Kaufman’s feature adaptation of same. Aerial effects produced using composited elements for that film failed to capture the necessary danger of flight, leading to a necessary step backward technologically, with in-camera techniques using models on wires shot live against real skies, an approach that probably wouldn’t feel out of place even today at FX WRX.

A decade into running the business, Webb and partner Graceann Dorse dared to expand the facility into what he describes as his “dream shop,” spending a year to renovate a building three times the size of the old space that had served as their incubator. “We just got in here last September,” he says. “Our main reason for building the new stage was so on any given day, people would be able to come and see how we do this work. Some West Coast clients like to just hang out, seeing what our R&D is trying this week. It’s another way to get the word out, so the next generation can find out about these new-old processes, while others get excited knowing this kind of work is still happening.”