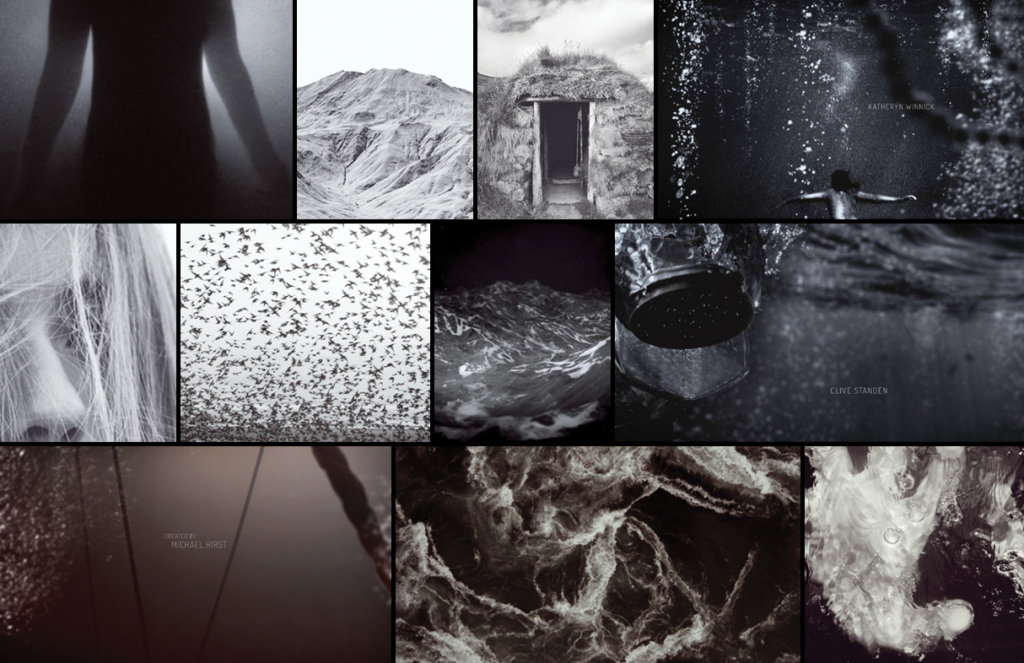

In addition to deeper characters and long-form narratives, today’s golden age of television has brought with it some true artistry in the form of title sequences. Gone are the days of actors smiling at the camera during the credits, intercut with clips from the show. In fact, the filmmakers at visual effects studio The Mill hadn’t seen a single frame of History Channel’s Vikings before they created the show’s stunning opening credits. A mini narrative in its own right, this 50-second sequence transports you not to a place, but a feeling. A feeling of impending doom that is somehow both tranquil and intimidating. It finds the beauty in danger and the acceptance of one’s fate.

Rama Allen, former executive creative director at The Mill, conceived the sequence for Vikings. And about five years before that, he created the True Blood opening sequence, which has heavily influenced modern title design.

Allen and his team had the rare opportunity to revisit his work for the fourth season of Vikings, a “super season” with 20 episodes instead of the usual 10. They expanded on ideas explored in the original sequence by adding the element of fire and enforcing the idea of Vikings spreading across the land like a plague. We chatted with Allen and Ryan McKenna, the editor for both sequences, about their conception and execution, and the opportunities granted to them by returning to this ocean of fire.

When an assignment like this comes to The Mill, does it get delegated to someone? Or do the directors pitch different concepts?

Rama Allen: In this case the History Channel came to me. They were fans of the True Blood title sequence, and they asked if I’d write some treatments and pitch for Vikings. I built a very small team, and we did a lot of research about Viking culture and history. We even went to the museum to look at cool Viking artifacts.

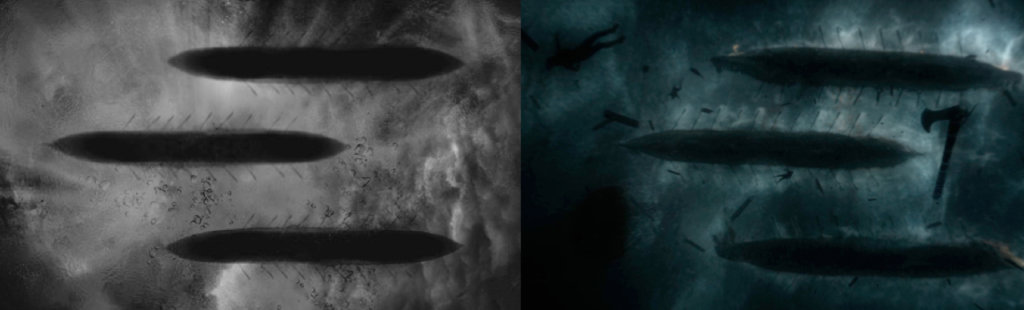

I wrote a couple different sequences, but the final sequence is based on a drowning dream I had one night while I was writing. When I woke up, the only image I could remember was looking up and seeing these dark objects on the surface of the ocean. It ended up becoming the second-to-last or third-to-last shot in the sequence. It’s basically celebrating the Vikings’ lust for death, their separation from their families, this sort of sinking into darkness and away from the light, and of course their love for the ocean.The idea was to do this drowning sequence, and it all centers around one character. You have these flickers of his gods, his family, his conquering, his life, and sex — he actually has sex with an ocean goddess at one part in his life — all of that good stuff. And at the very end, he realizes he’s not alone. He’s actually one of many people who are drowning in the ocean during a raid. That’s kind of the flow of it.

The other interesting factor was the music. I picked it before we began writing. I really wanted to use the Fever Ray track “If I Had a Heart,” and I actually pitched with it playing in the background. Fever Ray was super cool because she doesn’t typically license her music to anybody. But we sent her a rough edit, and she loved it. She said, “Okay, you can use my music.” So we got to keep the track.

You basically came up with the concept on your own before bringing it to the team?

RA: Yeah, I worked with a couple different people and, in particular, an art director named Audrey Davis. I had that drowning dream, I wrote it out, I picked the music, and I gave Audrey the idea. She basically art directed and built a bunch of style frames around it. We worked together on that, and that’s the pitch that ended up winning.

How did you shoot it?

RA: That’s a good story, actually. We really don’t have a budget for title sequences; they’re passion projects. And shooting an underwater sequence is really expensive. The DP I work with, Khalid Mohtaseb, has a friend in New Jersey who has a pool. So we spent two nights in New Jersey shooting in his pool, which, funny enough, is only six feet deep. That Viking you see in the title sequence is six foot two; so when he stood up, he wasn’t totally covered by the water. We actually shot the whole thing sideways. We turned the camera sideways, and that’s him standing in the pool and ducking underwater. Then we flipped it in post and built up the ocean around him.

We shot some stuff on the beaches in New Jersey as well. Then we did an aquarium tank shoot on the deck at The Mill. All of the elements like the coins, the axe, the particles, and stuff like that we shot here.

Besides shallow water and no money, what were some of the bigger challenges?

RA: Honestly, that’s where the stock footage came in. At The Mill, I can shoot tiny pieces of underwater footage, and we can use all the compositing power and the CG power. We can even build this ocean and make it feel massive. But to get the sense of scale above the water, I needed a storm. And short of flying to Iceland or something, which was out of the question for the budget, I needed to source stock footage to tell the story of the coming storm. In the beginning it’s raining gently; but by the very end, it’s this crazy storm, and there’s an island on fire, and all of this stuff. A lot of that came from stock.

For the second version of the title sequence — this new version we built — we did a lot of the same work. Ryan could probably speak to what he had to do for that, but I wanted to make the film feel even bigger. I wanted to get out of the water, and I wanted it to feel like a viral infection spreading across Europe. How do I get the feeling of moving through the woods, the campfire’s been left behind, these massive fields, and a large battle sequence? That’s where it became harder. I couldn’t shoot that stuff because there was literally even less money for this sequence.

Ryan McKenna: That probably happened right around the time we learned about Filmsupply. Whenever we go for stock footage, we don’t want things that feel like stock footage or that make it obvious from frame one what it is. We like imperfections and natural motion and movements that have similar sensibilities to the way we’d direct a DP if we were shooting it ourselves. We landed on maybe three different filmmakers that had really cool collections of smoke instead of just fire, or weirdly framed fire by the beach.

RA: It’s almost more about the camera behavior. When you go to other stock libraries, it’s like, “This is the object, and the camera is pointed at it.” It stinks and it doesn’t have that dance, that sort of improvised quality of finding the shot, or the camera moving to find the thing that’s interesting. With Filmsupply, more of the footage is shot by filmmakers, so it feels more real. It feels like we shot it because it was shot the way we’d do it.

Ryan, did you edit both versions of the sequence?

RM: Yeah, I did get to do both, which was cool. Rarely do you get to pick something up and then a few years later take another stab at it, preserve what you love, tweak it, and make it a little bit better. It was really fun.

It must have been tough to get all those pieces into a coherent 50 seconds. Did you have to kill a lot of darlings to fit it into that time frame?

RA: An enormous amount of darlings. Making the first sequence was even brutal because there were so many ideas. The whole thing is supposed to feel hallucinogenic, so you’re ramming all these flashes. When you’re dying, what are the last things you see? We’re flickering all these things in; and even though we probably put a zillion shots into 60 seconds, we never got all the ones we wanted. And then we got to make the new sequence, but first we had to chip away at the things we loved to add the new stuff. That was a brutal process.

Ryan, do you work on the sequence right down to the final effects?

RM: A little bit. But we have so many talented people who do all the finishing that I’m pretty much strictly offline. I’ll edit, and everything I edit gets passed on via EDL or XML to somebody else who’s gonna put it together with the highest res media. It’s liberating, in a way, to just be worried about that temporary version. That’s why it’s very difficult for me to be seduced by some of the new things in Premiere and other things that are great. It doesn’t really matter if the sequence doesn’t communicate all the things I need it to communicate.

RA: I would counter part of that, though. One of the reasons why I like working with you — why we cut so many things together — is because you’re a scrappy dude.

RM: Oh, I’ll play with everything.

RA: Yeah. He’ll be doing crude animations and overlays and rough composites, and then—

RM: I do everything, but it’s the comfort of knowing it’s temporary.

RA: Yeah, it’s all temporary.

RM: I’ll use After Effects, I will stabilize shots, I will comp things together, I’ll make maps and key things out, and I’ll make versions that are about 80 percent. It’s like that 80-20 rule. If you can make it look 80 percent quality, then somebody else can do the last 20 percent and make it perfect. But I can at least communicate the idea.

Tools

Camera: RED

Software: Final Cut Pro, Photoshop, NUKE, Flame, Maya, Baselight

Education: Rama Allen: Interactive Arts at Western Washington University Ryan McKenna: Film Production at Fitchburg State University

Credits

Filmsupply Contributors:

Design & Animation Studio: Mill+

Director: Rama Allen

Art Director: Audrey Davis

Head of Design Production: Danielle Amaral

Head of Content: Ian Bearce

Line Producer: Rich Schwab

Production Manager: Jon Simonetta

Director of Photography: Khalid Mohtaseb

Second Unit DP: Adam Carboni

Music: “If I Had a Heart” by Fever Ray